Last winter, a few weeks before coronavirus would hit the US, Barbara Kumari graduated with an MS in Family and Human Development, an MS in Psychology, a toddler and no income. Once the crisis hit pandemic levels, Kumari became one of the 100,000 employees Amazon hired to meet the sudden demand in its warehouses.

Kumari and her fellow new hires received two days of training, and from there on out, became cogs in the wheel. The day starts with a queue for a security check. Once in, employees sign in to a handheld scanner — which doubles as a location and productivity tracker — and start picking orders to place onto conveyor belts. Managers send instructions via scanner, email or an app. Breaks are usually taken alone, because the tables are spread six feet apart. When the shift is up, employees sign out, clock out, and leave.

“It is quite possible to go an entire day without verbalising anything to anyone, as it is all digitised,” Kumari said. “It is very independent work.”

The modern company is flat

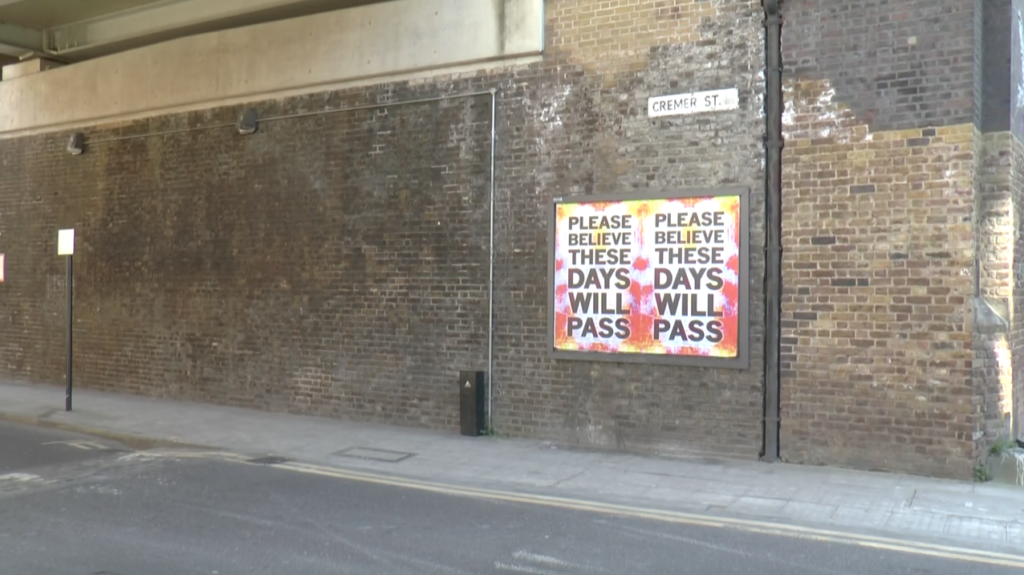

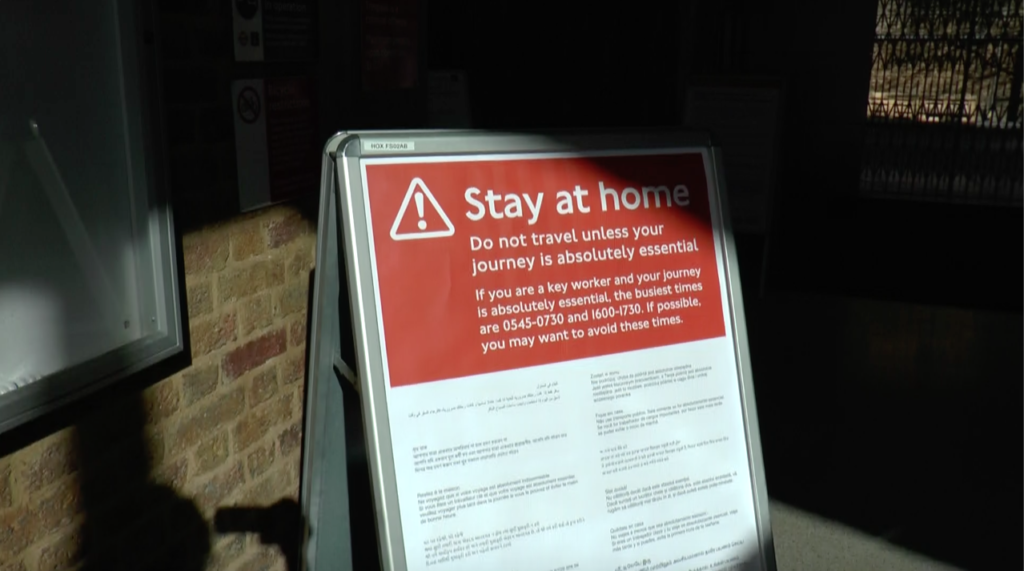

Autonomy has become a health necessity during the coronavirus pandemic, but it can also be alienating. Social distancing may prevent the spread of infection, but it can also hide the humanity of the service workers carrying out tasks behind the scenes, causing some companies to, as Kumari puts it, “treat employees as disposable robots”.

This autonomy also wouldn’t have been possible if it weren’t for one of the broad labour trends that’s taken place in the 50 years — one that Laetitia Vitaud, writer on the future of work, refers to as the “unbundling” of jobs, or the fragmentation of tasks within a job. Whereas mid-twentieth century companies were vertically integrated, with everyone from C-suite executives down to graphic designers, clerks and cleaners on the same payroll, today, these roles tend to be more stratified, turnover is higher and benefits are fewer.

Meanwhile, services that were once carried out by employees are becoming fragmented, as “some will be outsourced to other countries — everything that can be done remotely — and some will be outsourced to other companies that provide cheaper services, and the cheaper services are cheaper because the people are paid less,” Vitaud said. One example of this is a server in an office canteen; once a part of the company, today, that server is far more likely to be the employee of a third-party caterer that’s been contracted to manage that canteen. Meanwhile, chauffeurs and delivery couriers are now individual contractors on platforms like Uber and Deliveroo, giving rise to a new gig economy.

Now, as firms are looking for new ways to make fixed costs variable, “I think it’s likely unbundling will be accelerated by the pandemic,” Vitaud said. “And to make work a variable cost you will basically have more freelancers and short-term contracts … anything that’s variable and you can get rid of whenever you need to.”

Certain conditions of the pandemic, however, have made it so that even in-house employees suffer the same job insecurity. At the same time that high unemployment rates are leaving workers with very little leverage, social distancing measures are making it impossible to foster familiarity among colleagues — especially for those hired during the pandemic. “We’re afraid to make a mistake,” Kumari said, “as many of us know of the high turnover rate and how easily we can be dropped.”

For high-turnover warehouse workers, third-party caterers or freelancers, the premise is the same: the more interchangeable the worker, the less risk they impose to the employer because there’s no cost of retaining them. As a result, today’s low-wage work is interchangeable by design.

Such work tends to conjure factory workers in an assembly line, but this can extend to cognitive roles as well, a new labour market Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri describe in their book, Ghost Work. These are the workers behind all the menial tasks still too difficult or expensive to be done by a computer — transcribing audio into subtitles, moderating social media content flagged as obscene, or recording sentences in their native language for an AI translation tool to pick up their speech patterns.

The tasks, dubbed “microtasks”, are paid for on a piece rate, often amounting to below minimum wage in the countries from which they’re hired. And just as the assembly line worker will never build the entire car, the digital “crowd worker” may never know what the overall project is they’re working on. Chances are, they won’t even know the company that hired them, as most tasks are regimented through third-party platforms like Clickworker or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a cheeky nod to the 18th-century chess-playing automaton that was really controlled by a human.

Unlike the assembly line worker, however, overseen by a line manager, the crowd worker is a self-employed contractor — a reality that can be far more cruel, as there’s no one to report to when a task takes longer than advertised or a contract is terminated due to an unforeseen illness. There is no regulatory framework for such workers either; the private contractor designation exempts them from labour laws.

“The hope of the book is that people see we are not describing niche jobs,” said Gray. “Any work, like that done by [Kumari], that can be scheduled, managed, shipped, and billed via APIs and the internet makes it harder to see and value the worker. Devaluing workers — eliding their very presence — creates ghost work conditions.”

Now, companies that are being made to extend their work-from-home policies may also need to re-evaluate their labour force. “There’s this idea that a crisis like this one — and also the fact that more people work remotely — is accelerating the way that we are organising work and redefining tasks,” Vitaud said, leading some to automation or outsourcing.

Growth in the gig labour market may also be supply-driven. As small businesses continue to go bust and workers are left cash-strapped or confined to their homes, many are turning to platform-based jobs, in what tech reporter Brian Merchant has dubbed “the Amazonification of the planet”.

Indeed, one study from the Oxford Internet Institute (OII) found an increase in the online labour supply in the United States, including both the microtaskers described in Ghost Work and freelancers bidding for projects on platforms such as Upwork. In some domains such as tech, supply has outpaced demand, leading to a “relatively clear tightening of the market,” said Fabian Stephany, OII researcher and co-author of the study. The result is less and less pay commanded per project.

One worker affected by the squeeze is Chris Garman, who ramped up his search for online employment when the store he worked at shuttered for good. Lately, the only gigs he’s been able to net are the occasional paid research surveys, about $3 per task at most. “As far as anything that could be considered a decent income, I haven’t been able to find anything legitimate since the US unemployment started rising to historic levels,” Garman said. “I think now that so many people with degrees are all of a sudden looking for work, many of these employers are hiring people who are overqualified for some positions.”

“Keep your social distance”

Not only are precarious workers placed at a safe distance from their employers — whether through social distancing on the warehouse floor or the anonymity of online platforms — they’ve also been rendered invisible to the consumers they serve, especially now that white collar workers are holed up at home. Every batch of groceries bought online versus in store is one less employee-customer interaction. The class divide no longer merely refers to a pay gap.

For Amazon customers, “I do think it’s a lot harder to sympathise, not because they don’t care necessarily, but because one isn’t exposed enough to the situation to feel for it,” Kumari said. Before working there, Kumari recalls ordering from Amazon for its ease and low prices, without once considering how the packages arrived. “Customers just know that it arrives fast. They don’t realise that employees are isolated, underpaid, belittled, pressured,” and “endangered”, she said. “I don’t blame them because I still remember that state of oblivious purchasing well.” Now she refuses to shop on Amazon, despite an employee discount — not just because of the workers’ higher risk of infection, but for the dehumanisation they face. “I don’t want someone to feel that way filling my order,” she said. “I’d rather risk going to the store to get what I need than to order from Amazon, even after the virus, because of how they treat their workforce.”

The alienation has even extended among co-workers, as social distancing measures have created a new means of limiting talk. “Most feelings are gauged through shouted complaints,” Kumari said. “We struggle to communicate above the distance and noise very intimately and must take to Reddit and other organisations.” This has put collective bargaining almost out of the question (indeed, when Chris Smalls — who staged a walkout to call attention to a lack of health safety — was fired last March, Amazon chalked it up to Smalls’ breach of social distancing).

For digital gig workers, the distance extends well-beyond two metres. The way most online work platforms are set up make it impossible to know who else is working on a project — for all they know, it could be their next-door neighbour or someone in India.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world may never see who is translating their TV captions or trawling their social media feeds for hate speech. While public outrage can be a useful tool for bringing about reform (the shock of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire is widely credited for America’s first labour laws), “I think there’s a lack of general awareness that these jobs exist, actually,” Stephany said, adding that when people think of gig workers, delivery couriers are usually first to spring to mind. Even in economic indicators, these workers are invisible. Whether the gigs are plentiful or sporadic, decently paid or not, their work status is still self-employed — a flaw in the unemployment rate that’s “always been the elephant in the room,” Stephany said.

The same goes for the accounting books. When one firm contracts another to, say, field calls on their customer service hotline, when this is tabulated in the costs, “it looks like a normal phenomenon of buying services and goods,” Vitaud said. As a consequence, it’s difficult to measure how much of a company’s labour force is outsourced.

The regulation of precarious work is also tricky. The more interchangeable the task, the more likely this is to be true — and in the case of online, low-skill work, the labour supply is limitless. “Arguably, this is one of the first truly global markets — the market of online gig work,” Stephany said. “Let’s say, for example, the ‘All-American MTurk Workers’ unionise, and they put pressure on Amazon Mechanical Turk or they call for minimum wage, then it might be possible that their jobs are increasingly going to be outsourced to countries where, for just simple economic reasons, people could afford working for lower wages.”

Of course, for non-remote gig workers like Uber drivers and Deliveroo couriers, global outsourcing is not an option. Now that their work has been deemed “essential”, however, the pandemic may represent a turning point. “Covid-19 certainly brought to light the importance of gig workers for the everyday functioning of society,” said Funda Ustek-Spilda, researcher and project manager at the Fairwork Foundation, which advocates for platform workers.

“We have also observed that most platforms rolled out policies and measures to protect their workers against the potential risks of working during the pandemic,” Ustek-Spilda said, adding that it would be difficult to justify a return to “business-as-usual” by rolling these back. “If it is possible to provide financial assistance to a worker for getting ill during the pandemic, why would it not be possible to provide similar assistance to them when they break a leg a year from now?”

Autonomous but without autonomy

Isolating work can instil a lack of agency — often the very lack of agency that landed workers there in the first place. “Many may wonder why in the world we would stay in this condition,” Kumari said. “We aren’t necessarily naive, uneducated, or have a death wish working there at this time. We just haven’t gotten other options.”

Others may be isolated by the virus itself. Garman is the sole caretaker of his disabled mother, who also has an autoimmune disorder, which puts her at critical risk for Covid-19. As such, high pay is not his first priority — ”I would take less to work from home, as long as the pay was reasonable and I could cover my necessary household expenses,” he said. With no university degree, and for the sake of his mother’s health, any on-site job out of the question, Garman is happy to toil behind a screen.