Consumers spent the 2010s getting used to tech and big data as constant companions for life’s complicated banalities – nutrition, exercise, step goals or keeping up with loved ones. The arrival of at-home streaming platforms and same-day Amazon delivery also standardized convenience and accessibility to an unprecedented extent. Its byproduct is a cyber-happy culture whose followers live by curated algorithms and trust the addicting power of immediate results.

Imagine Americans’ reactions, then, when an app broke the Iowa caucuses.

Two weeks ago, during the first primary vote of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, precinct chairs flagged as early as midday that they were struggling to report results in a new app designed intently for the Iowa elections. When the app stopped working, officials flooded the state Democrats phone lines. Chaos ensued; many couldn’t even connect over the volume of callers. No backup plan existed for the failing software.

Candidates and voters alike jumped off the sinking ship and accused the Iowa Democrats of gross incompetence. Other more problematic calls from disenfranchised voters and Trump supporters suggested election tampering. These voices were a loud, eye-opening plurality over social media.

The Iowa caucuses do not decide a presidential election. Rather, as the first contest of primary season, they can help voters gauge the electability of the field of candidates. As a predominantly white, Christian state, Iowa results are always scrutinized and weighted by pundits, yet early victories can give campaigns an early boost into swing state primaries.

But this year, the dysfunctional IowaRecorder app upstaged any political momentum.

By the time the full Iowa caucuses results came out, a full four days later, it was already old news and met with a shrug. Instead, the airspace was filled with numerous reports of the bugging app, how the software bypassed functionality checks and why Shadow Inc., a firm no one had ever even heard of before, was at the heart of rumors of an elaborate plot to rig the results.

But the chaos of the Iowa caucuses transcends political calamity. For many, the election software’s failure evoked an existential fear that technology could disrupt the integrity of the electoral process. The last decade has witnessed and replayed the tech-trust tradeoff debate across a number of platforms that collect and analyze data – this includes social media, wearable technology and DNA testing. The implication behind collecting data is that someone, somewhere, can find and access your unprotected information within a server.

But when this precarious relationship is tried within the context of democracy, the risks shake the very foundation of the institution. Amid uncertainty, voters are left with a vacuum to speculate, bringing out deep insecurities to the mainstream that stem from living in a politically divisive and mistrustful era.

This mistrust is dividing leftists among themselves, too, and dismantling past precedent of party fidelity. A staggering 28 Democrats launched a presidential campaign this election cycle. This compares to the highly-critiqued 23 in the 2016 Republican field, which at the time signaled deep party disunity and infighting. As ties emerged between Shadow, Inc. and former South Bend, Indiana mayor Pete Buttigieg’s campaign, many Democrats were quick to suggest meddling by the Democratic establishment to put a centrist candidate ahead of the pack.

We are going into the decade ahead with enormous potential in what technology can do. In just ten years, we will certainly expand access to healthcare, refine gene editing software, teleport across continents with virtual reality and so much more. But while doubt and speculation persist towards tech’s role in our elections, it’s best to stick to analog. Iowa has already done enough damage to the institution’s trust and faith in our political actors.

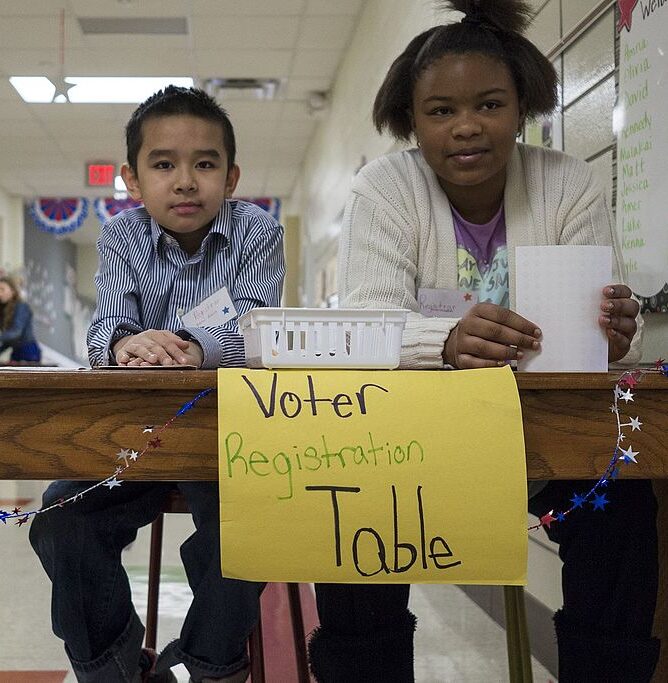

Image: Phil Roeder/Wikimedia Commons